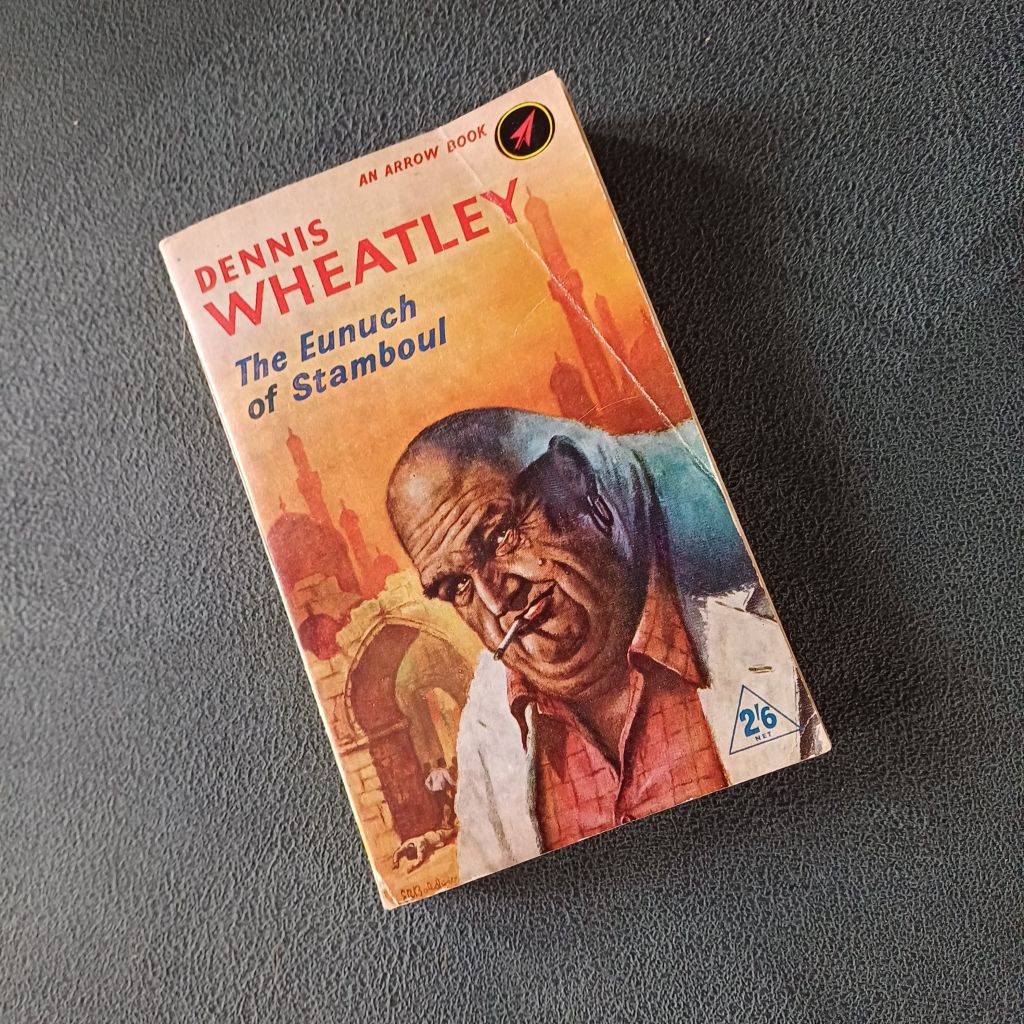

I found this book by accident in a charity shop and picked it up simply because it had the word “eunuch” in the title.

Apparently, it was filmed as the “Secret of Stamboul” in 1936 (also known as “The Spy in White”), starring the gorgeous Yorkshireman, James Mason.

The story follows the very British Swithin Destime as he travels to Istanbul on a secret mission following his ejection from the army for gallantly coming to the rescue of Diana Duncannon. With names like Swithin and a couple of Sirs, and a Turkish prince, you know what kind of story is going to follow!

Our hero is lovingly described as –

Not overburdened with brains, he possessed charming manners and a delightful personality.

Page 13

Wheatley’s use of English is an absolute joy; he was a creature of his time – the early autumn of the British empire, already hollowed out yet managing to trade on its past “glories”. There is a lot of British exceptionalism – a sort of “You can’t shoot/imprison me; I’m British!” kind of thing, which one can only smile at now. Here’s an example:

No policeman, whether he be black, white, yellow, or brown lays his hands with impunity on the property of His Britannic Majesty’s accredited representatives

Page 246

All that said, I couldn’t help but warm to Swithin’s character. There were a number of end of chapter cliff-hangers that were genuinely tense – I looked forward to picking the book up again the next night.

Returning to what drew me to the book, the eunuch! On page 64 we first hear of an old palace eunuch now as chief of police. Described as a sneaky, spying, blackmailing type.

When we finally meet him it’s clear we are supposed to know that he’s a villain – Wheatley takes a loot of time making sure we loath the guy:

There, above them, his enormous bulk filling the great breach in the wall stood one of the strangest looking individuals they had ever seen. He was a tall man with immensely powerful shoulders but the effect of his height was minimized by the gigantic girth. He had the stomach of an elephant and would easily have turned the scale at twenty stone. His face was even more unusual than his body for apparently no neck supported it and it rose straight out of his shoulders like a vast inverted U. The eyes were tiny beads in that great expanse of flesh and almost buried in folds of fat, the cheeks puffed out, yet withered like the skin of last year’s apple, and the mouth was an absurd pink rosebud set above a seemingly endless cascade of chins.

Page 96

The eunuch also has a high pitched voice; indeed the historical records show that pre-pubescent boys were used to create eunuchs, so that would be correct.

Wheatley goes out of his way to paint the eunuch in an unfavourable light. The last Sultan’s daughter, Ayşe Osmanoğlu, described the actual last chief eunuch, Cevher Agha, as a loyal and charitable servant rather than the villainous or grotesque figure often portrayed in Western fiction of that era. The reality of the human is eclipsed by the need to see eunuchs as less than human.

Indeed, in the revolution that cost him his life he was hanged not for any crime, but because he refused to reveal the location of his master’s treasure. Wheatley described hideous extra details for the death of the old chief eunuch, which was made up for the story – perpetuating western prejudices against eunuchs.

The fact that our villain is a eunuch is irrelevant to the story: it doesn’t actually add anything other than playing on stereotypes of easterners with “corrupted morals”. The same goes for his enormous bulk. Nothing is added to the story aside from a bit of humour as his chins wobble. It does make it easier to play upon cultural physiognomic preconceptions of ugly or deformed people being wicked. Think Richard III and his hump or the ugly sisters in Cinderella: we are taught form an early age that if somebody looks ugly, they are likely to be wicked.

We might expect a modern telling of the story set in the same period to have a paraprosdokian revelation at some point that makes the reader gasp.

In that respect, Wheatley’s action story is entertaining only because it trades on familiar tropes; it is unoriginal, and its depiction of the eunuch is lazy, damaging, and entirely unnecessary to the plot.

Leave a comment