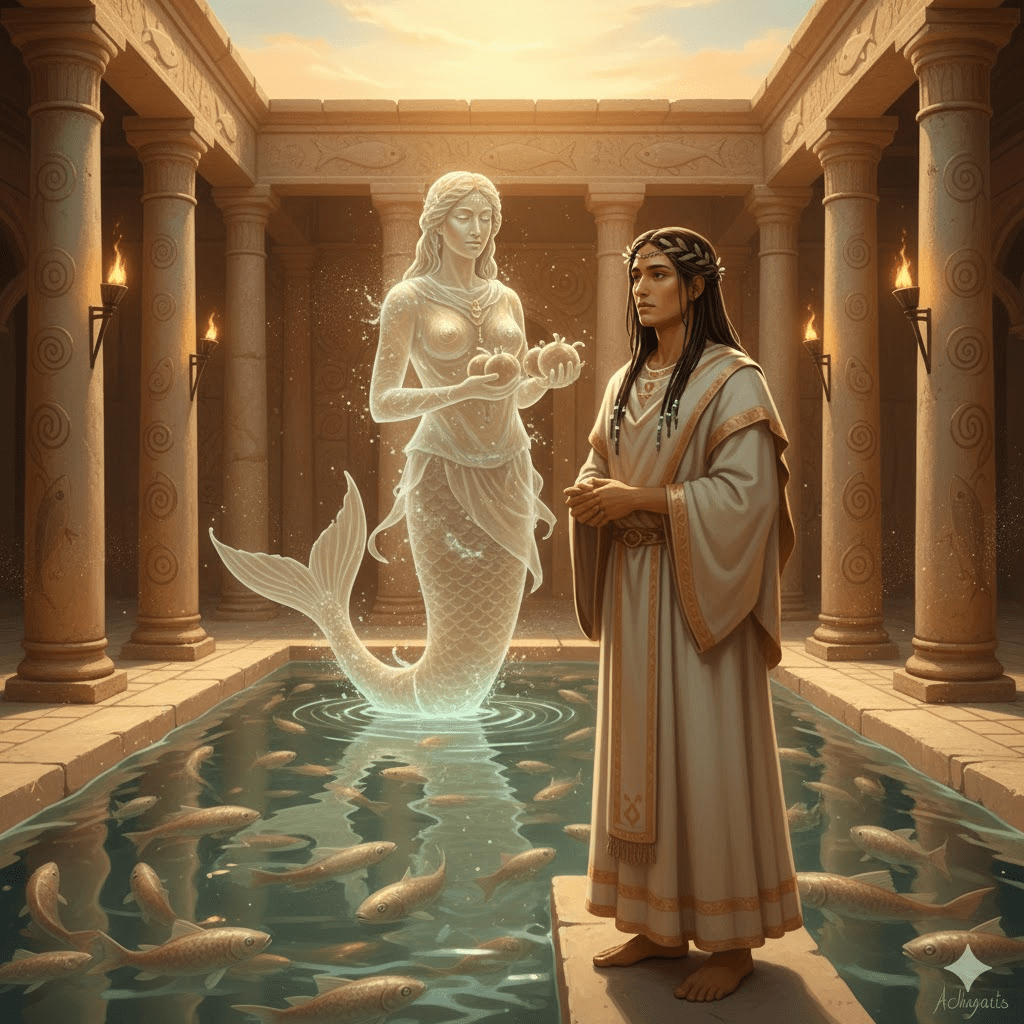

There are goddesses who rule the earth, and goddesses who rule the heavens – but Atargatis, the great Syrian Mother, ruled the waters in between.

Half woman, half fish, she was said to have thrown herself into a lake out of grief or shame, transformed into a mermaid and reborn as divine. Her temples shimmered with fountains and pools full of sacred fish. Worshippers brought offerings of doves and perfumes; priests, more daringly, brought their flesh.

Atargatis, or Derketo as the Greeks sometimes called her, was worshipped across northern Syria and beyond. Her greatest sanctuary stood at Hierapolis, a city Lucian of Samosata described in his De Dea Syria – a place where the goddess’s image, richly dressed and enthroned, sat before a pool of living fish so holy that no one dared eat them. Her consort was the storm god Hadad, who brought rain from the sky to meet her waters below. Together they formed the eternal marriage of earth and sky, male and female, fertility and destruction.

But it was her priests who made the cult infamous.

Lucian tells us that her temple attendants, called galli (the same word later used for the priests of Cybele), were eunuchs. They wore soft garments, jewellery, and long hair, and served the goddess through music, dance, and ecstatic ritual. They were not merely attendants; they were living symbols – men who had offered up their generative power to the goddess who created life itself. Their self-castration was a sacrifice, yes, but also a transformation: an act that blurred the boundaries between male and female, mortal and divine, flesh and water.

To serve Atargatis was to cross a threshold – between the land and the sea, the masculine and the feminine, the human and the sacred.

A Sister of Cybele, but Not Her Twin

Atargatis is often mentioned in the same breath as Cybele, the Phrygian Great Mother whose own eunuch priests, the galli, performed similar rites. But they were not quite the same goddess, nor the same story.

Cybele’s myth centres on her mortal lover Attis, who in a fit of divine madness castrates himself beneath a pine tree. The priests who followed her repeated his sacrifice in ritual imitation, expressing grief, devotion, and rebirth. Their castration was a re-enactment – myth made flesh.

Atargatis’s priests, by contrast, were not acting out a mythic narrative. Their castration was an offering of fertility back to its source – a purification rather than a tragedy. If Cybele ruled the mountains and wild beasts, Atargatis ruled the waters and the womb. One throbbed with frenzy; the other flowed with mystery. Cybele’s rites were about passion and death. Atargatis’s were about transformation and surrender.

Yet both cults attracted those who lived between categories – people whose identities did not fit neatly into their societies’ definitions of male and female, sacred and profane. In serving these goddesses, they claimed a kind of holy ambiguity – something I recognise more and more as a form of truth rather than confusion.

Devotion and the Body

There’s something haunting about the idea of giving up one’s generative flesh for the sake of a goddess. It isn’t just mutilation; it’s metamorphosis. A radical offering of the self – both body and identity – to something greater, purer, more encompassing.

For the galli of Atargatis, this was devotion in its rawest form: faith expressed through transformation. They left behind not just their fertility, but their social role, their gender, their place in the ordinary world. They became something other, consecrated to the divine in body and spirit.

In that act I see echoes of my own journey – though mine was not done in the frenzy of ritual, but through the long, deliberate conversation between self-knowledge and necessity. Still, I recognise the pull toward purity, the desire to strip away what feels false or redundant, to live in truth even when that truth sets one apart.

Atargatis’s priests lived between land and sea, between man and woman, between the sacred and the shunned. Perhaps that’s what it means to belong to her: to find holiness in in-betweenness.

References and Sources

- Beard, Mary, North, John, & Price, Simon. Religions of Rome, Volume 1: A History. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Lucian of Samosata, De Dea Syria (2nd century CE), esp. sections 14–51.

- Roller, Lynn E. In Search of God the Mother: The Cult of Anatolian Cybele. University of California Press, 1999.

- Budin, Stephanie Lynn. The Myth of Sacred Prostitution in Antiquity. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Lightfoot, J. L. Lucian: On the Syrian Goddess. Oxford University Press, 2003 (excellent annotated translation).

Leave a comment