Trans is a fascinating area for eunuchs and nullos. Many of us identify as trans, yet continue to present in ways that align with our birth-assigned gender – often male – which means we avoid some of the visibility (and risk) that binary trans people face. As such, we don’t suffer from much of the stigma that binary trans people do – for us invisibility is both a cloak of defence and a reason for omission. For binary trans people, visibility is both a curse and a blessing – I feel that it puts them at greater risk from transphobes. Whilst fem-presenting eunuchs and nullos may suffer the same transphobia through their increased visibility, this post isn’t about transfem, but about transmasc.

Transgender people do not have to have surgery to identify as trans. Neither do they need a particular gender expression. Some argue that the broadness of the term ‘trans’ is creating confusion within the community – but narrowing it by demanding surgery or a certain lifestyle only adds cruelty – especially since any kind of surgery – whether top, bottom, or masculinisation/feminisation, is both privately expensive or there is the excruciating NHS waiting times.

A significant, yet unknown, number of trans people do not survive to have surgery. The system seems almost designed to thin the numbers out through “misadventure” or making life unliveable: the cost of transphobia isn’t abstract – for too many, it’s fatal.

I identify as trans in a broad sense – non-binary, eunuch – but I’m aware that right now, the basic rights of binary trans people are under attack. So I don’t want to take up oxygen that should be going toward their protection. I stand with them, even as I inhabit a slightly different corner of gender.

I’m less into the twinky types, but Ian Harvie – phwoar! He is very much my type of guy!

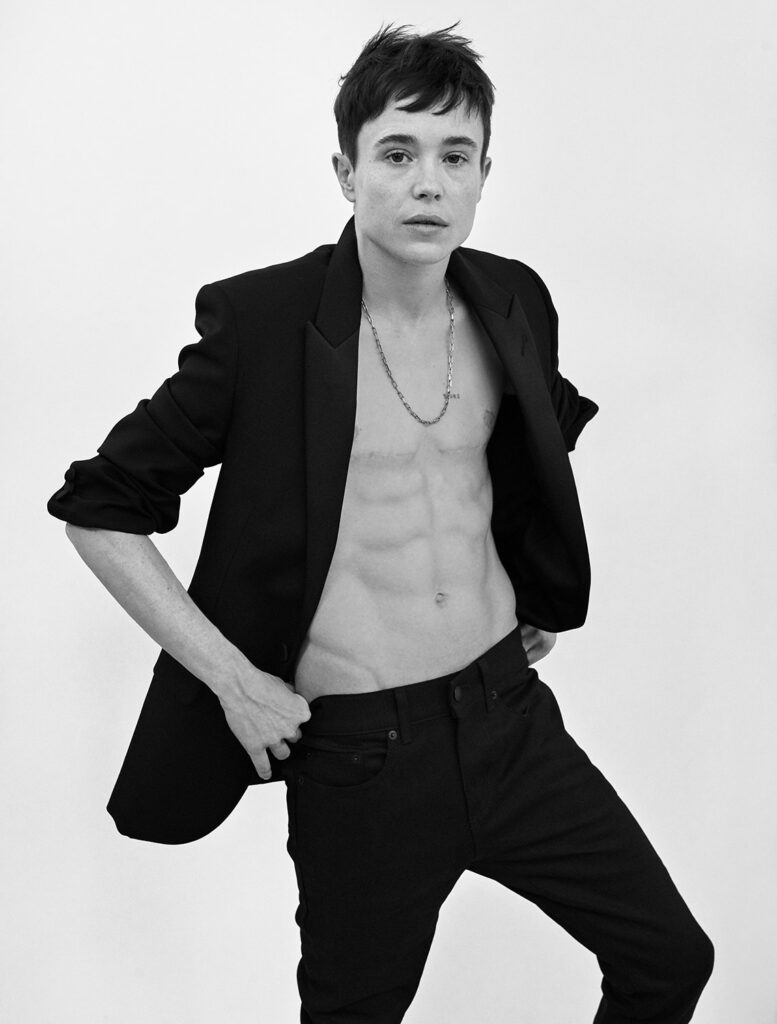

Elliot Page

Once one of Hollywood’s most recognisable queer women, Elliot Page’s coming out as a trans man in 2020 was seismic. But it wasn’t just about visibility – it was about vulnerability, joy, and finding ease in his own skin. Whether on screen, in interviews, or shirtless on Instagram, Elliot’s masculinity is disarming: gentle, honest, and utterly unafraid to feel.

Chella Man

Chella Man is a walking disruption – in the best way. Deaf, Jewish, Chinese-American, genderqueer, and transmasc, he brings every part of himself into his activism and art. His masculinity defies white, cis, able-bodied norms – and instead radiates from a place of fluidity, softness, strength, and deep-rooted self-acceptance. Muscular, yes – but also soulful and smart.

Lucas Silveira

As the frontman of The Cliks, Lucas Silveira made history as the first openly trans man signed to a major record label. With a gravelly voice, raw lyrics, and a powerful stage presence, Lucas embodies a rock-star masculinity that’s both gritty and self-aware. His journey through transition and public scrutiny adds layers to the swagger – a reminder that badass and transmasc are far from mutually exclusive.

Thomas Page McBee

Thomas Page McBee was the first trans man to box at Madison Square Garden – but he’s not just a fighter. He’s also a writer, thinker, and explorer of what it means to be a man. In his memoirs, McBee doesn’t just document his own transition – he interrogates masculinity itself: its origins, its dangers, and how it can be reshaped. His masculinity is curious, ethical, and ever-evolving.

Ian Harvie

A stand-up comic and actor, Ian Harvie was one of the first openly transmasc performers to make it big in Hollywood. He uses humour to crack open hard topics – like gender, shame, and sex – and finds power in playfulness. His masculinity is confident, flirtatious, and wickedly funny – reminding us that transmasc expression doesn’t have to be serious to be real.

Why it matters

Transmasculinity is often the most overlooked stripe in the rainbow. While transfeminine people are subject to constant attack, transmasc people are frequently erased – presumed to be cis men, or treated as if their identities are less “serious” or urgent. This invisibility can be a shield, but it can also be a silencer.

Representation of trans men and transmasc people matters because it challenges lazy assumptions about masculinity, transition, and what it means to “be a man.” It makes space for softness, for strangeness, for humour and grief and contradiction. It reminds us that masculinity can be claimed, not just inherited – and that it’s not something you need to prove, but something you get to shape.

For those of us whose relationships to our own bodies and genders are complicated – whether we’re eunuchs, nullos, non-binary, or simply queer in our skins – transmasc visibility offers possibility. Not a mirror, exactly, but a constellation of fellow travellers who’ve carved their own paths through the fog.

Leave a comment