After the initial struggle to come out, I was mostly content to define myself as “a gay man”. Coming to terms and exploring that identity was more than enough to begin with. I was happy being a “chicken” (as the old Polari speaking gentlemen back-in-the-day would have said – a twink in modern parlance).

I have always been attracted to particular versions of masculinity, strong and kind, roguish and a little intimidating.

The gay masculine spectrum

The male gay community consists of so many shades of man, from the quietly domestic to leather-and-chains; from rugby lads to Broadway dancers. And you can be one or many of those “types”. However, mainstream culture tended to erase or simplify this diversity into one stereotype that was palatable for the cis- heteros to digest.

Much of what we call masculinity is performative – a set of behaviours, appearances, and attitudes that signal “manliness” to others. For many gay men, especially in the past, exaggerating these performances was a form of self-protection. Deep voice. No wrist flicks. Talk football. Don’t show too much emotion. This kind of “performative masculinity” was often the price of safety or acceptance, both in straight society and even among other gay men. But it’s not just about hiding – sometimes it’s also about play. Gay culture has long been brilliant at parodying, remixing, or reclaiming these performances: from drag kings to leather daddies, we’ve found ways to make masculinity queer, camp, and complicated.

The world has moved on and gay masculinity can inhabit the entire spectrum; it’s accepted that gay men can be soldiers or nurses, as camp as a row of tents or as butch as a bulldog. Take your pick as to whether the soldier is the camp or the butch one!

It was the AIDS crisis that exposed a number of “straight” men as gay (or bi), blowing the prejudices apart that gay men were all pansies:

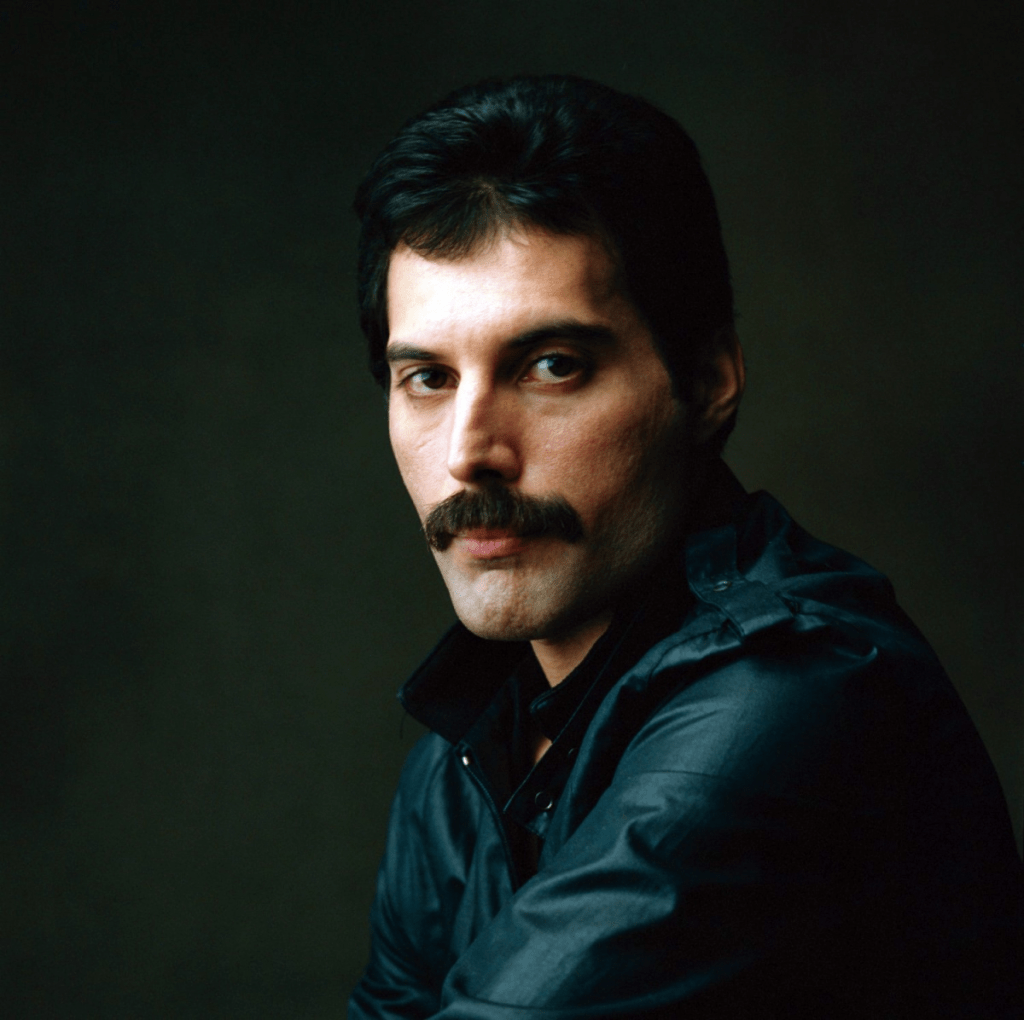

Freddie Mercury, the electrifying frontman of Queen, lived much of his life under a cloud of speculation regarding his sexuality. Though he never made a grand public declaration during his lifetime, his identity as a gay man became widely acknowledged, especially after he confirmed he had AIDS just one day before his death in 1991. In many ways, his coming out was posthumous – and all the more powerful for it. At a time when the HIV/AIDS crisis was ravaging the gay community and stigma ran high, Mercury’s revelation forced the world to reckon with the humanity behind the headlines. A figure of flamboyant showmanship and staggering vocal power, he became an unexpected icon of gay masculinity – complex, private, and defiant – and helped shift perceptions of what a gay man could be.

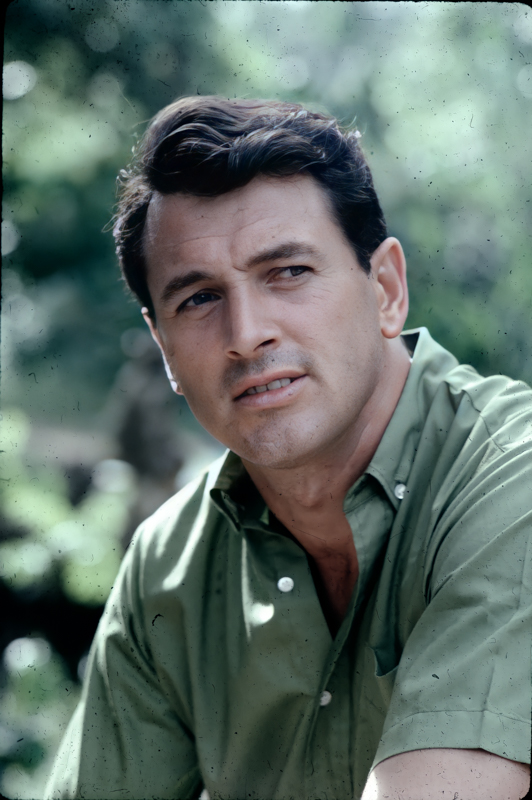

Rock Hudson was the epitome of 1950s American masculinity – tall, broad-shouldered, and romantically entangled with the leading ladies of Hollywood. But behind the studio-curated façade, he was a closeted gay man navigating a fiercely homophobic industry. His private life became a matter of public record in 1985 when he was revealed to be suffering from AIDS, making him the first major celebrity to be associated with the illness. Hudson never publicly came out, but the revelation of his diagnosis cracked the silence surrounding both AIDS and homosexuality in a profound way. It jolted the American public, challenging entrenched assumptions about who could be gay – and forcing uncomfortable conversations into the mainstream. In doing so, Hudson became an unlikely trailblazer, his stoic screen persona giving way to a more human, vulnerable legacy.

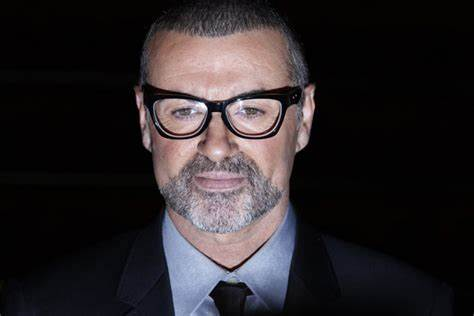

George Michael was a pop superstar whose voice and charisma made him a global sensation in the 1980s and 90s. While speculation about his sexuality swirled for years, it wasn’t until his arrest in 1998 for a “lewd act” in a public toilet that he was effectively outed to the world. Rather than shrink from the scandal, Michael responded with wit and unapologetic honesty, reclaiming the narrative with the video for “Outside” – a tongue-in-cheek celebration of public sex and queer defiance. From that point on, he embraced his identity more openly, becoming a proud voice for the gay community and a staunch advocate for sexual freedom. His journey from pop heartthrob to queer icon was messy, defiant, and deeply human – and it highlighted the tension between public image and private truth in a world still uncomfortable with complex gay identities.

Leo Varadkar became Taoiseach (Prime Minister) of Ireland in 2017, making him not only one of the youngest leaders in the country’s history but also the first openly gay one – a striking development in a country that had only legalised homosexuality in 1993. His sexuality, while never his central political identity, was nevertheless profoundly symbolic. As the son of an Indian immigrant and a gay man leading a predominantly Catholic nation, his very presence in office marked a transformation. Varadkar’s quiet, competent masculinity stands in contrast to louder or more stereotypical expressions – it is a masculinity grounded in thoughtfulness, responsibility, and modern Irishness. His role in championing the 2015 marriage equality referendum added emotional weight to his political persona, showing that the personal and political are never truly separate for queer leaders.

Luke Evans, the Welsh actor and singer, presents a more contemporary example of gay masculinity that defies stereotype. Openly gay from early in his career, Evans quietly rejected the usual media circus around ‘coming out’ by simply living his truth. He rose to stardom with roles in action-heavy films like Dracula Untold, Fast & Furious 6, and Beauty and the Beast, all without compromising his identity. Unlike earlier generations who were forced to hide or sanitise themselves for public consumption, Evans navigates Hollywood with a confident ease that signals cultural progress. His visibility challenges the lingering notion that gay men can’t convincingly play masculine leads – and helps widen the space for younger queer people to imagine themselves in any role.

Gareth Thomas was a towering figure in the world of rugby long before he came out as gay in 2009 – in fact, that was part of the impact. As captain of Wales, he embodied the very image of rugged, physical masculinity. His coming out, then, sent shockwaves through a sport still steeped in machismo and silence around sexuality. Thomas didn’t fit the stereotype of the “gay man”, and that was exactly the point: his openness challenged the false divide between athletic prowess and queerness. Later, he disclosed his HIV status and became a campaigner for awareness and compassion, turning vulnerability into strength. His story is a reminder that gay masculinity doesn’t need to be softened or sanitised to be accepted – it can be fierce, bruised, proud, and powerful.

Why it matters

- Each of the people above was a shock to the assumptions and prejudices that surrounded what a gay man could (and could not be). Some felt their coming out betrayed the young women who had crushed on them, or the straight men who had idolised them as models of masculinity.

- It is important that all versions of gay masculinity are represented as this is both validating for men like them and destabilising of the common prejudices that would otherwise imprison gay men.

- As seen in Gareth Thomas’ story, masculinity in gay men has often been erased, hidden, or disbelieved – “If he’s that butch, he can’t be gay.”

- All expressions of gay masculinity are valid as masculinity is, in fact, like so much else in life, a spectrum not a binary – we all are part of the same divine pantheon.

From the sacred defiance of Freddie Mercury to the quiet strength of Leo Varadkar, gay masculinity occupies its rightful place among the gods.

Leave a comment