According to a commonly shared story, the anthropologist Margaret Mead was supposedly asked by a student what she thought was the earliest sign of a civilized society. There are many variations of the anecdote, but the general details are similar: To the student’s surprise, Mead replied that the first sign of civilization is a healed human femur – the long bone that connects the hip to the knee.

https://www.sapiens.org/culture/margaret-mead-femur/

Mead proceeded to explain, as the story goes, that wounded animals in the wild would be hunted and eaten before their broken bones could heal. Thus, a healed femur is a sign that a wounded person must have received help from others. Mead is said to have concluded, “Helping someone else through difficulty is where civilization starts.”

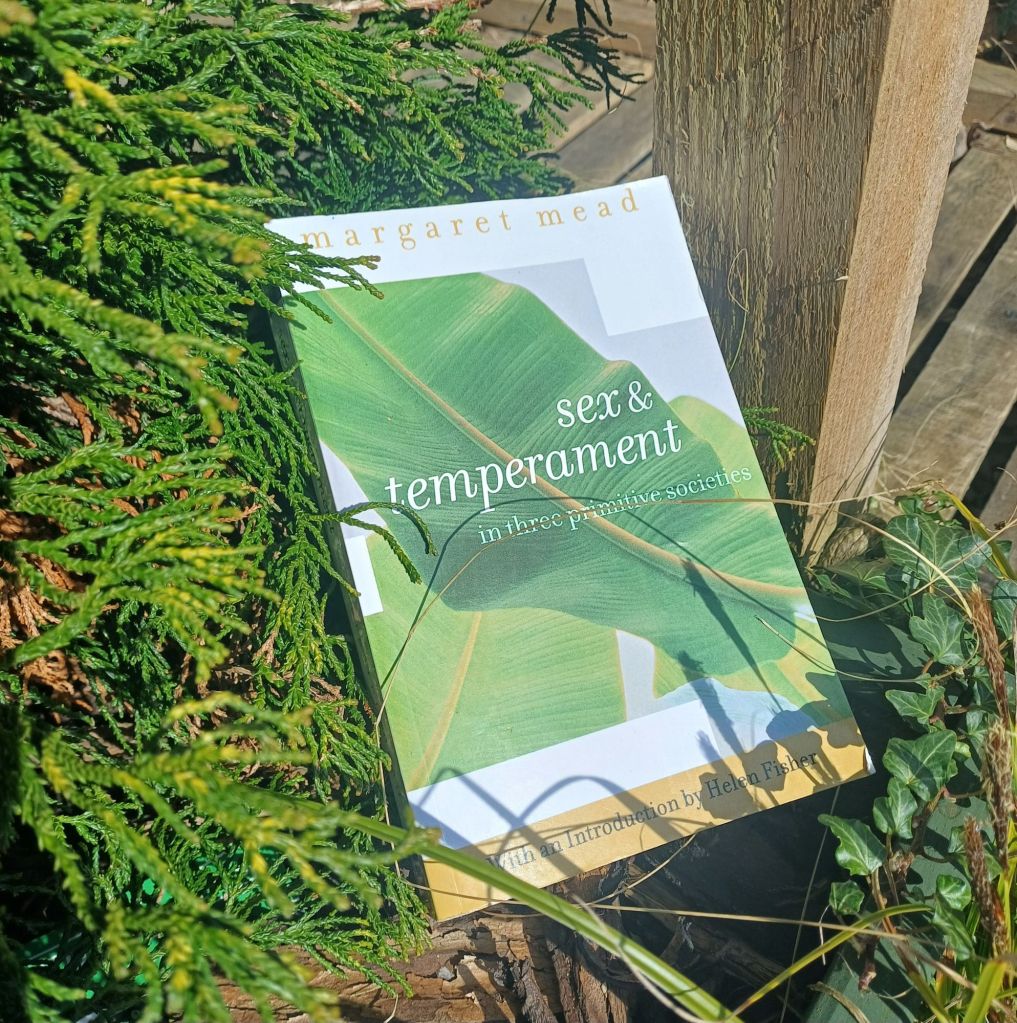

I heard this (supposed) Margaret Mead quote a little while ago. It’s disappointing to discover that she may not have said it, but it piqued my interest about her and her studies. I can believe that she may have said it, or something like it.

This story, whether apocryphal or not, paints a picture of civilization rooted in compassion – something very different from the dystopian vision favoured by Elon Musk and co, who believes that compassion and empathy are a bug in humanity that must be eradicated in order for his version of civilization to flourish. I find his views on civilization abhorrent and excoriable.

The first tribe she investigates have the most delightful attitudes to life: they are unacquisitive, generous, unambitious, and uncompetitive – their highest virtues are cooperation and sharing. They are generally so civil towards each other that they need to train special men to plan and organise long term projects – recognising that something of the sociopath has is uses. Interestingly, these people lay down their position at the earliest opportunity to retire and join in the regular society of cooperation enjoyed by the rest of this people.

Whilst the sexes of this first tribe do perform different roles, the the rearing of children is a shared duty that the father and mother take equal share in; the language even uses the same terms for carrying a child (ie being pregnant) of both men and women. In that respect, this particular tribe does shake up our western ideas of mother and father that have only recently started to change to one of shared responsibility in summer families. This tribe’s extended family means of raising children, seems almost idyllic compared to how it is done in “civilised” societies: children never want for life and affection.

There are specific activities associated with each sex, such as men hunt and women carry things. That latter activity does bring a smile to my face: there has been a particular blind spot in Western dress regarding female coded clothing whereby pockets have, until recently, only been routinely included in male coded clothing, forcing women to carry bags … which men and children proceeded to fill with things that they didn’t want to carry!

Males can be just as nurturing as females. Being emotional isn’t a female monopoly, but is a learnt trait. Aggression and competition are learnt traits. Acquisitiveness and greed are a learnt traits.

The second tribe, both men and women are quarrelsome. That said, this is clearly a partriachy where men are in control on the household.

Whilst women didn’t have much power, girl children were valued much more than boy children. Father’s would tend to want boy children killed as male heirs were a threat.

The third and final tribe, on the surface appears to be a patriarchy, with inheritance being patrilineal and polygyny being the norm … however, in practice, the women wield the power: they initiate sex, they control the finances, men actually sit on the edge of society bickering with their neighbours – tolerated and patronised (the irony) by their women-folk.

… we may say that many, if not all, of the personality traits that we have called masculine or feminine are as lightly linked to sex as are the clothing, the manners, and the head-dress that a society of a given period assigns to either sex.

Page 262

She likens different temperaments as colours, then assigns these colours to the various groups among the three tribes, and explains that the temperaments effectively describe a gender spectrum (page 265). This is int 1935.

She further goes on to state that cultures are man made (page 264), and uses the term “social construct” to describe how roles in societies are are assembled and distributed, whether by sex, age, caste, or some other arbitrary attribute.

There was no homosexually among either the Arapesh or the Mundugumor.

Page 274

I include this quote to illustrate a criticism that is made of Margaret Mead in the introduction: she tends to make sweeping generalisations. In this particular example, she hasn’t understood that homosexuality isn’t always named as such. Can she be sure that she got behind all the taboos in each culture? In such small societies, perhaps the that man and woman cannot find like-minded people to explore their sexuality. Even in Western culture, homosexuality hasn’t always been identified, expressed, or named in the same way.

Mead implies that Western psychiatric diagnoses of gender ‘disorders’ are culturally relative, not objective truths. Modern psychologists should (and do) understand that gender is a social construct and has no objective reality.

The conclusion is that having a nurturing nature is a result of nurture not nature!

If we are to achieve a richer culture, rich in contrasting values, we must recognise the whole gamut of human potentialities, and so weave a less arbitrary social fabric, one in which each diverse human gift will find a fitting place.

Page 300 (the last sentence of the book)

It’s a powerful conclusion – and one we’re still struggling to live up to.

Leave a comment